Banning nuclear explosions protects the environment

- Nevada: over 900 nuclear tests were conducted at the Nevada Test Site, most of which were underground. Radioactive contamination of the area remains to this day, both in the soil and the water table. Although radiation levels decline over time, radioactivity of the water table in the worst affected areas prohibits consumption of water from it for thousands of years.

- Bikini: although the last test on the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands was in 1958, the former tropical paradise remains a wasteland. An International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) survey conducted in 1997 discouraged permanent resettlement of the Bikini Island because of radiological conditions.

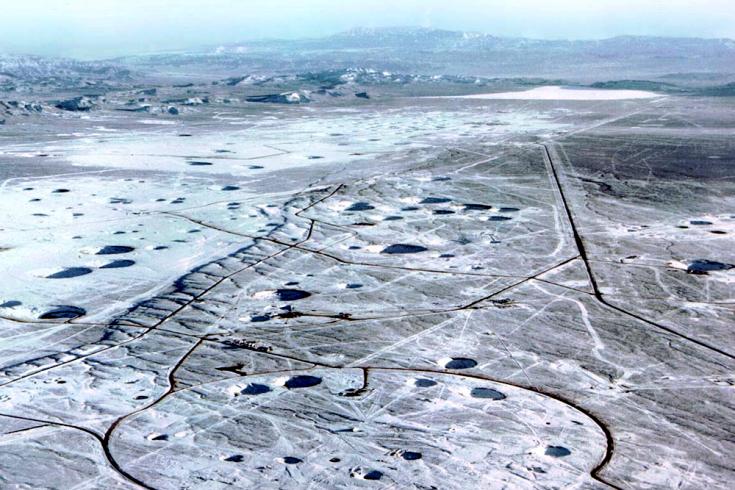

- Kazakhstan: over 450, mostly underground, nuclear tests were conducted at the Semipalatinsk test site. They accelerated the process of desertification of the area which continues to this day. Radioactive contamination of the environment severely reduced economic activity in the area.

- Muroroa: nuclear testing at this Pacific atoll caused the leakage of radioactive fission products into the ocean and the food chain. Testing also caused environmental damage, triggering landslides, tsunamis and earthquakes.

Craters as remnants from nuclear explosions mark the landscape at Semipalatinsk.

Some of the test sites have been abandoned with little or no environmental protection. Novoya Zemlya, in particular the surrounding Barents and Kara Seas, and the Mururoa Atoll are examples. Without effective management of the legacy of radioactive waste from the tests radioactive material is being released into the seas and into the ground, eventually ending up in the food chain.

The CTBT protects the environment

As well as significantly strengthening nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), by putting a permanent halt to nuclear testing worldwide, will forever prevent the disastrous effects of nuclear testing on human health and on the environment.

Recent political support for the Treaty has raised the prospects for its entry into force which would also cement the security it offers the environment.

Craters from nuclear tests at Nevada Test Site.

The CTBT is an integral part of the international non-proliferation and disarmament regime and played an important role at the recently concluded Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Two States ratified the Treaty while at the conference, the Central African Republic and Trinidad and Tobago, bringing the number of ratifying States to 153. Other States, including Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Guatemala, made strong pledges towards initiating concrete steps towards the ratification of the CTBT in their countries. Many of the participating States called on the hold-outs to follow suite and sign and ratify the Treaty.

The final document of the NPT Review Conference, which by consensus was agreed upon by 189 countries, reaffirms the importance of the Treaty’s entry into force as “a core element of the international nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime”. It calls on all nuclear-weapons States to ratify the CTBT with all expediency” and to encourage other States whose signature and ratification is needed for the Treaty’s entry into force to sign and ratify.

The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, the CTBTO, builds the tools that will monitor compliance with the ban on nuclear testing once the Treaty enters into force. A globe spanning network of over 300 monitoring stations is part of the global verification regime along with an international data centre and on-site inspections to detect nuclear explosions anywhere on the planet.

The environmental impact has been one of the considerations in building the stations. Some are located in national parks or in environmentally protected areas. Special procedures have to be followed when building and running these stations. In such cases, CTBTO has involved national environmental institutions in order to respect and implement relevant regulations.

When building Infrasound station IS36 in an environmentally protected area on New Zealand’s Chatham Island, construction work was carried out without heavy machinery.

For example, when installing infrasound station IS36 within a protected conservation reserve on the New Zealand Chatham Island, special care was taken to prevent any damage to the forest. Wheel barrows replaced heavy machinery during the installation and some pipes of the infrasound arrays were bent around trees.

Also in the southern hemisphere, at infrasound station IS02 at the southernmost tip of Argentina, the station’s communication setup had to be adjusted to respond to national requirements for environmentally protected areas. Instead of opting for radio communication with a number of radio towers, much less intrusive fiber optic cables were installed.

But even when stations are not built in national parks or protected areas, special care is consistently taken to minimize the potential impact on the environment. Many monitoring stations are located in isolated areas and need an independent fuel supply to run them. At the radionuclide station RN39 on the island Kiritimati (Christmas Island) in the Pacific Island State of Kiribati, special diesel tanks were designed to prevent the possibility of leaks that could contaminate the shallow water table on the island.

Some array elements of infrasound station IS36 on New Zealand’s Chatham Island have bent pipe to protect trees.

The CTBTO recognizes that climate change threatens the planet and is committed to doing its share to move towards the goal of a climate-neutral UN. Along with its sister international organizations at the Vienna International Centre, the CTBTO has undertaken initiatives to reduce energy consumption, curtail air travel, and encourage use of mass transit:” Tibor Tóth, Executive Secretary of the CTBTO.

Since June 2007, the CTBTO conducts all job interviews via video-conference, thereby saving more than 200 air trips over the past two years. Office equipment has been replaced with eco-friendly equipment. Copiers have been adjusted to produce double-sided copies by default.

The CTBTO continues to explore additional ways of conducting its work in as sustainable a manner as possible. Examples of good practices in other UN and international organizations are examined to develop similar policies.

Special precaution was taken when installing a diesel tank on Christmas Island, Chile, to prevent contaminating leaks.

Monitoring data and technologies of the CTBT verification regime have a great potential to be applied in the civil and scientific realms. Many of these opportunities have an environmental benefit, such as: the use of data for the research of the oceans and their biodiversity; climate change research; meteorology and studies of the atmosphere; research of the break-up of ice-shelves and the creation of icebergs.

The CTBTO is sharing its data with tsunami warning centres in the Indo-Pacific region to help protect the public against the dangers from tsunamis. Other possible uses of its technologies remain untapped. Atmospheric transport modeling, used to backtrack or forecast the movement of radioactive substances, can contribute to civil aviation safety by assisting in the monitoring of volcanic ash plumes, a hazard that recently halted European air traffic.

4 Jun 2010