6 and 9 August 1945: Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Every year, Japan hosts peace memorial ceremonies that bring together people from all corners of the globe, sharing a common goal to put an end to nuclear testing and the use of such weapons.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, marking the end of World War II, demonstrate the devastating power of nuclear weapons. These were the only instances of atomic bombs used in conflict, causing unimaginable destruction, and giving rise to a unique survivor group, known as hibakusha.

These survivors, categorised by their exposure to the blasts and their aftermath, share first-hand experiences of the reality of nuclear warfare.

In today's global landscape, the stories of the hibakusha serve as poignant reminders of the deep human toll brought about by nuclear explosions. Their legacy motivates us to strive for a world where such destruction is both difficult to comprehend and unattainable.

Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima

The impact of atomic bombs

On 16 July 1945, Robert Oppenheimer and other U.S. scientists tested the first ever atomic bomb at a site located some 340 kilometres south of Los Alamos, New Mexico.

With World War II continuing in the Pacific, plans advanced for the deployment of nuclear bombs against Japan.

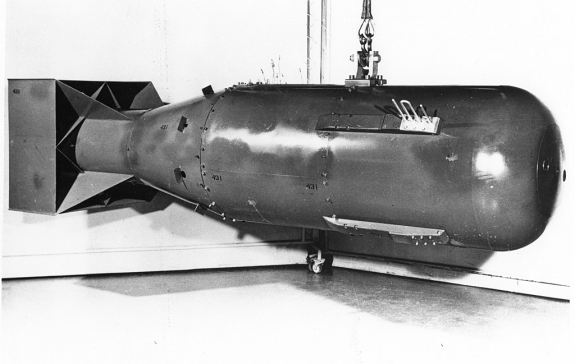

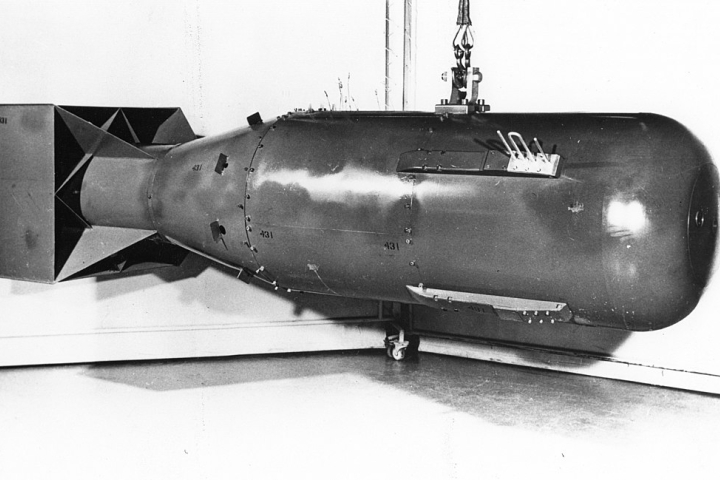

On 6 August 1945, at 08:15, the first ever atomic bomb was dropped on the centre of Hiroshima. ‘Little Boy’ was a gun-type atomic bomb. It used a simple design by firing one piece of uranium 235 into another, triggering a powerful explosion with about 15 kilotons of force.

Upon detonation, it produced a fireball that raised temperatures to 7,000 degrees Celsius. The blast also generated shockwaves exceeding the speed of sound.

These shockwaves, coupled with the radiation released, killed thousands, and transformed Hiroshima, a city with wooden and paper buildings, into a fierce inferno.

After the explosion, a heavy downpour of black rain, carrying radioactive fallout, caused widespread contamination. Those who approached the blast's epicentre in search of the missing were exposed to this radiation.

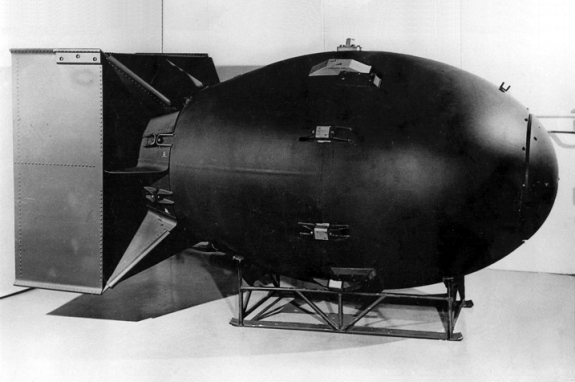

Three days later, in the early hours of 9 August, a second U.S. aircraft took off from Tinian Island in the Pacific Ocean. The nuclear device it transported bore the codename 'Fat Man'.

This was a more advanced plutonium-based bomb that had undergone trials during the ‘Trinity test’. While originally intended for the city of Kokura as its primary target, the airplane's crew shifted to Nagasaki due to a dense layer of clouds.

Reports differ on the casualties from the bombings, with estimates as high as 166,000 deaths - mainly civilians.

Over 2,000 nuclear tests were conducted after 1945, contributing to the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the development of arsenals far more powerful than the bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nagasaki Peace Park dedicated to commemorating victims of the 1945 atomic bombing.

A ban on nuclear test explosions for a safer world

Following decades of public campaigning and multilateral negotiations, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) opened for signature in September 1996.

The Treaty bans all nuclear test explosions everywhere, by everyone, and for all time. While adherence to the CTBT is nearly universal, for it to enter into force, it must be ratified by all 44 States listed in its Annex 2, for which nine ratifications are still required.

The CTBTO has established an International Monitoring System (IMS) to ensure that no nuclear explosion goes undetected. The data collected by the IMS serves multiple purposes, including disaster mitigation, such as earthquake monitoring and tsunami warning. Additionally, it supports research in various fields, ranging from whale migration, climate change studies, to predicting monsoon rains.

‘Little Boy’, the codename for the first nuclear weapon used in warfare

‘Fat Man’, the atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan

8 Aug 2011